Improving MedDRA/J Coding Accuracy with a Fine-Tuned Text Embedding Model

Abstract¶

Existing Japanese Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA/J) search tools support exact and partial matches but struggle with paraphrased, synonymous, or colloquial expressions not present in the dictionary, increasing the operational burden on coders. We aim to enhance the efficiency and accuracy of MedDRA coding by employing advanced natural language processing (NLP) techniques, specifically a fine-tuned text embedding model. We utilized MedDRA/J terminology and an in-house adverse event database comprising 71,813 combinations of expressions and lowest-level term (LLT) codes, covering 45,395 unique adverse event expressions. We compared several methods: Jaccard index for partial match simulation, Word2Vec embeddings, GLuCoSE v1 and v2 embedding models, and our fine-tuned model based on GLuCoSE v2 enhanced with domain-specific data using triplet margin loss. Our results demonstrated that the fine-tuned GLuCoSE v2 model significantly outperformed conventional methods. Specifically, the model achieved an nDCG@20 of 76.2%, Recall@20 of 90.8%, and Recall@100 of 95.4% when utilizing 50K entries from the in-house database. Moreover, re-ranking experiments using large language models (LLMs) further improved the ranking of appropriate LLT candidates. In conclusion, integrating advanced NLP models and effectively utilizing in-house data significantly improves the accuracy and efficiency of MedDRA/J terminology searches.

Authors¶

Shoya Wada a,b; Masaharu Okamoto b; Kento Sugimoto b; Yasushi Matsumura b,c; Katsuki Okada b; Shozo Konishi b; Takuya Hara d; Jun Kato d; Tadashi Matsuno e; Saki Nakano e; Toshihiro Takeda b

Affiliations¶

- a: Department of Transformative System for Medical Information, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Osaka

- b: Department of Medical Informatics, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Osaka

- c: National Hospital Organization Osaka National Hospital

- d: Pharmacovigilance Department, Drug Development and Regulatory Science Division, Shionogi & Co., Ltd.

- e: Data Science Department, DX Promotion Division, Shionogi & Co., Ltd.

- ORCiD: Shoya Wada — https://

orcid .org /0000 -0001 -7055 -1009

Conference metadata¶

- Conference: MEDINFO 2025

- Date: August 11, 2025

- Location: Taipei, Taiwan

- Poster Session: Aug11-065 — Poster Session Monday (13:15–14:00, 1F Poster Area)

- Poster Size: A0 (841 × 1189 mm)

Keywords¶

- MedDRA coding

- pharmacovigilance

- natural language processing

- large language models

Introduction¶

Pharmaceutical companies in Japan are required under the Act on Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices to collect and report information on adverse events, infections, and defects associated with post-marketing pharmaceuticals and medical devices. An essential process in this compliance is Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) coding, an international terminology used for regulatory communication, which is manually performed and demands significant time and cost.

The MedDRA Japanese Maintenance Organization provides a MedDRA/J search tool supporting exact and partial matches for MedDRA/J terminology. However, when encountering expressions not present in the dictionary—such as paraphrased, synonymous, or colloquial descriptions—operators must recall and search for likely terms, increasing operational burden.

Natural language processing (NLP) technologies have been applied to improve the accuracy of MedDRA terminology searches. Some studies have demonstrated the utility of semantic similarity-based searches for medical terminology using neural network-based embeddings in SNOMED CT, ICD-10-CM, and ICD-10. However, few reports focus specifically on the utility of embeddings for MedDRA. Recently, research leveraging Transformer-based models to use more context-aware embeddings for improving search accuracy has become increasingly active. In this study, we address gaps in MedDRA coding by employing state-of-the-art NLP models to enhance search efficiency and accuracy, especially for Japanese-language expressions not directly found in existing MedDRA terminology.

Specifically, we evaluate the utility of embedding representations (Sentence-BERT) in MedDRA terminology searches, compared to conventional methods such as text matching and Word2Vec-based embeddings. Additionally, we demonstrate how effectively utilizing the in-house database improves search accuracy.

Methods¶

Data Collection and Preparation¶

We used MedDRA/J ver. 27.0 (March 2024) as the primary reference, excluding terms with the “Non-current flag in Japanese,” resulting in 71,339 terms, including synonyms.

We utilized an in-house Shionogi & Co., Ltd. database containing 244,438 records where each adverse event could link to multiple Lowest Level Term (LLT) expressions. This database included expressions that registrants had reinterpreted from raw text to facilitate MedDRA coding for regulatory reporting, making the content more accessible to users. By removing entries with combinations already included in MedDRA/J, we focused on 71,813 unique combinations, which cover 45,395 unique adverse event expressions and are challenging to detect through simple exact matches.

The data were split into training (n=50,667; used for fine-tuning the text embedding model and utilized to expand MedDRA/J terminology for searching user queries), development (n=10,482; to determine optimal parameters during fine-tuning), and testing (n=10,664) datasets. We stratified the dataset based on the primary System Organ Class (SOC) of each LLT code. To maintain consistency, we ensured expressions associated with multiple LLT codes were not split across datasets.

Comparison Methods and Baseline Models¶

- Jaccard Index: Used to simulate partial match search as a baseline, measuring similarity between sets akin to unordered keyword searches.

- Word2Vec: We used Japanese Wikipedia Entity Vectors from Tohoku University, performing mean pooling of word embeddings for comparison.

- GLuCoSE models (PKSHA Technology Inc.): GLuCoSE v1 is a Japanese text embedding model based on LUKE. GLuCoSE v2 is an enhanced model fine-tuned using distillation with large-scale embedding models and multi-stage contrastive learning.

- Our Fine-tuned Model: Based on GLuCoSE v2, further fine-tuned using MedDRA/J terminology and the in-house training dataset. We employed triplet loss, using the query’s associated Preferred Term (PT) as the anchor, the query as the positive example, and an LLT from a different PT but within the same High Level Term (HLT) as the negative. Hyperparameters were optimized using Optuna with 100 trials.

Re-ranking Evaluation¶

Given the promising results of language generation models in re-ranking tasks across domains, we employed re-ranking to enhance the accuracy of suggested LLT terms. We identified challenging cases where correct LLTs ranked between 20 and 100 by our fine-tuned model. We provided a prompt with the top 100 LLT candidates for re-ranking based on semantic similarity to the query text.

- Random Shuffle: A random shuffling of LLT terms served as a baseline.

- Local Large Language Models (LLMs): Llama 3.1 Swallow 8B and 70B instruct (Q5_K_S), quantized models trained on the Swallow corpus, fine-tuned on Japanese and English instruction datasets.

- Cloud-based LLMs: GPT-4o-mini (2024-07-18) and GPT-4o (2024-08-06).

Evaluation Metrics¶

We focused on the top 20 results to align with practical user behavior. Mean average precision (MAP) assesses how well relevant candidates are ranked higher. Normalized discounted cumulative gain at 20 (nDCG@20) measures the quality of the top 20 retrieved results, emphasizing the ranking of relevant items. Recall@20 and Recall@100 evaluate the coverage of relevant results within the top 20 and 100 retrieved items.

Results¶

Table 1 summarizes the performance metrics for each method. The Word2Vec approach had the lowest performance, while the Jaccard index and GLuCoSE v1 showed comparable results. GLuCoSE v2 significantly outperformed all other models. Our fine-tuned model achieved nDCG@20 of 76.2%, Recall@20 of 90.8%, and Recall@100 of 95.4% with 50K in-house entries.

Table 1. Performance metrics of different methods in MedDRA/J terminology search¶

| Method | MAP | nDCG@20 | Recall@20 | Recall@100 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Word2Vec | 20.6% (19.8–21.4) | 24.9% (24.1–25.7) | 34.3% (33.2–35.3) | 45.1% (44.1–46.2) |

| Jaccard index | 33.8% (33.0–34.6) | 40.1% (39.3–40.9) | 51.5% (50.6–52.5) | 59.6% (58.6–60.5) |

| GLuCoSE v1 | 32.0% (31.2–32.9) | 39.5% (38.7–40.3) | 52.8% (51.9–53.8) | 62.8% (61.9–63.7) |

| GLuCoSE v2 | 45.0% (44.1–45.8) | 53.1% (52.3–53.9) | 63.6% (62.7–64.5) | 71.2% (70.4–72.0) |

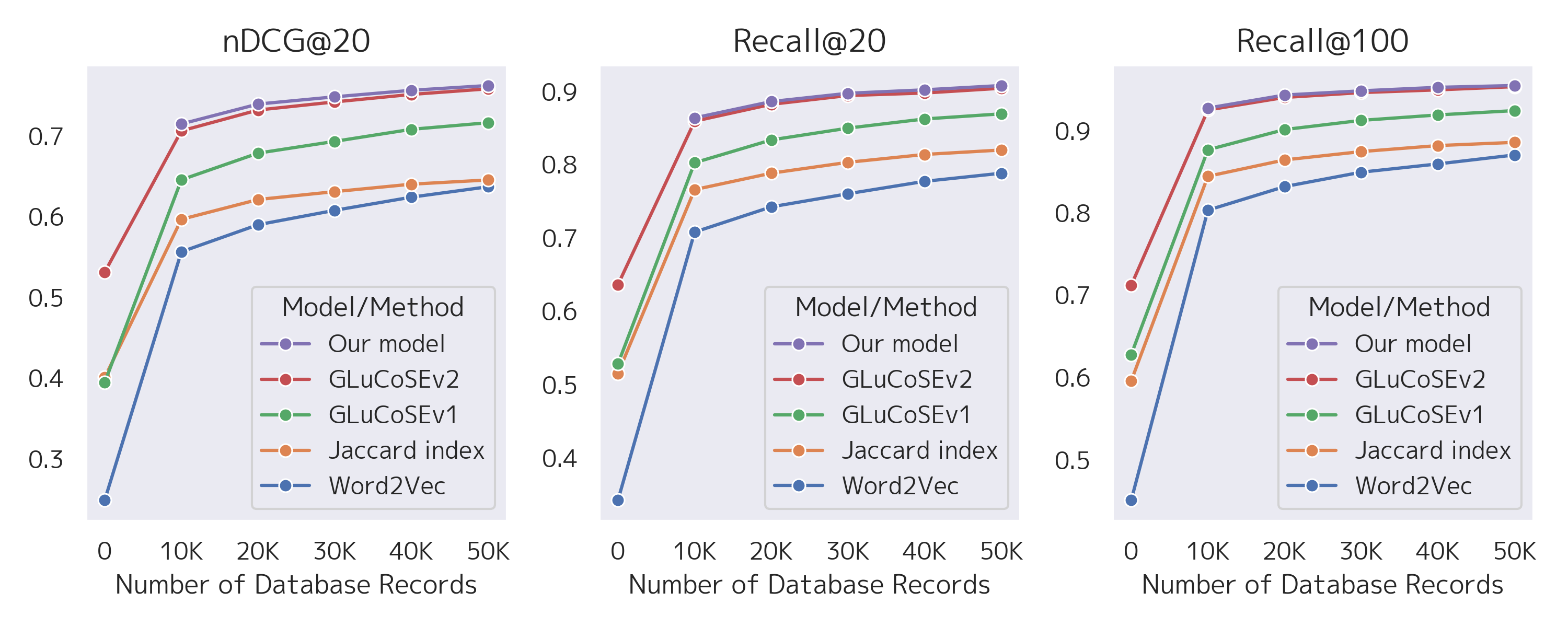

Increasing the volume of the in-house database dramatically improved nDCG@20, Recall@20, and Recall@100 across all methods (see Figure 1). Compared to GLuCoSE v2, our fine-tuned model achieved a 0.4–0.9% improvement in nDCG@20 without a statistically significant difference in Recall.

Figure 1:Effect of in-house database volume on model performance metrics (nDCG@20, Recall@20, Recall@100) across methods.

Table 2 presents the re-ranking evaluation results for 195 challenging cases. All four LLMs significantly outperformed random shuffling. Cloud-based LLMs were statistically more accurate than local LLMs in Recall@20. Interestingly, differences between lightweight and larger models within the cloud-based LLMs (GPT-4o-mini vs. GPT-4o) and local LLMs (8B vs. 70B) were not statistically significant.

Table 2. Re-ranking performance of large language models compared to baseline (195 challenging cases)¶

| Method | MAP | nDCG@20 | Recall@20 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random shuffle | 4.8% (3.4–6.2) | 6.1% (4.0–8.2) | 17.7% (12.3–23.1) |

| Llama 3.1 Swallow 8B (Q5_K_S) | 23.7% (18.7–28.8) | 41.4% (36.6–46.2) | 44.9% (37.9–51.9) |

| Llama 3.1 Swallow 70B (Q5_K_S) | 27.5% (22.2–32.7) | 38.3% (33.2–43.4) | 51.5% (44.5–58.6) |

| GPT-4o-mini (2024-07-18) | 32.0% (26.7–37.2) | 40.6% (35.2–45.9) | 66.2% (59.5–72.8) |

| GPT-4o (2024-08-06) | 35.7% (30.2–41.2) | 39.4% (34.0–44.8) | 69.5% (62.6–76.4) |

Discussion¶

Advanced text embedding models can suggest appropriate LLTs for expressions not directly included in MedDRA/J terminology. With 130 million parameters, our model is efficient enough for CPU processing, making it practical for local use.

Expanding the search with the in-house database had a more significant impact than introducing the latest embedding model. Even the lowest-performing Word2Vec method outperformed GLuCoSE v2 without in-house data when using 10K entries, highlighting the substantial benefit of organizational data.

The modest improvements of our fine-tuned model over existing models may be due to the limitations of triplet margin loss, which only leveraged the hierarchical structure of MedDRA/J up to HLT, PT, and LLT levels. Future work could explore advanced tuning techniques, like listwise ranking learning with higher-level hierarchies, although quantifying similarities between LLTs remains challenging.

Re-ranking experiments indicate that LLMs can enhance MedDRA/J suggestion systems, both locally and cloud-based. While tokenized MedDRA/J, including all LLT and synonyms, exceeds LLM context windows, LLMs become feasible after narrowing down initial candidates, as in our study. A practical workflow might include a re-ranking option when initial suggestions are insufficient.

Two significant limitations exist: (1) we use query expressions that may reflect registrants’ interpretations rather than original inputs; and (2) we have yet to perform an external validation.

Real-world AE expressions and generalizability¶

Real-world adverse event (AE) expressions, often reinterpreted from raw text, are crucial for capturing linguistic variations absent in MedDRA/J. For example, a frequently encountered colloquial note such as 「胃が痛い」 (lit. “my stomach hurts”) does not directly match any MedDRA/J dictionary entry, yet our fine-tuned model correctly maps it to 「胃痛」 (lit. “Gastralgia”). By learning from in-house AE expression–LLT pairs, the model improves ranking quality for such paraphrased or colloquial inputs.

Beyond MedDRA/J, this approach is transferable to other clinical ontologies (e.g., ICD, SNOMED) provided appropriate training data are available, suggesting broader applicability for coding support in diverse terminology systems.

Conclusions¶

Using an advanced text-embedding model significantly improves the accuracy of MedDRA/J’s Japanese term search. Leveraging an in-house adverse event database further improved recall and ranking metrics, demonstrating the usefulness of organizational data. These findings suggest that advanced NLP technology could substantially improve MedDRA coding efficiency and accuracy, leading to more effective pharmacovigilance practices.

References¶

- Souvignet J, Declerck G, Asfari H, Jaulent MC, Bousquet C. OntoADR: A semantic resource describing adverse drug reactions to support searching, coding, and information retrieval. J Biomed Inform. 2016;63:100–7. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2016.06.010

- Combi C, Zorzi M, Pozzani G, Moretti U, Arzenton E. From narrative descriptions to MedDRA: automagically encoding adverse drug reactions. J Biomed Inform. 2018 Aug;84:184–199. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2018.07.001

- Martinez Soriano I, Castro Peña JL, Fernandez Breis JT, San Román I, Alonso Barriuso A, Guevara Baraza D. Snomed2Vec: Representation of SNOMED CT Terms with Word2Vec. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 32nd International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems (CBMS); 2019; Cordoba, Spain. IEEE; 2019. p. 678–83. doi:10.1109/CBMS.2019.00138

- Lin C, Lou YS, Tsai DJ, Lee CC, Hsu CJ, Wu DC, Wang MC, Fang WH. Projection Word Embedding Model With Hybrid Sampling Training for Classifying ICD-10-CM Codes: Longitudinal Observational Study. JMIR Med Inform. 2019 Jul 23;7(3). doi:10.2196/14499

- Böhringer D, Angelova P, Fuhrmann L, Zimmermann J, Schargus M, Eter N, Reinhard T. Automatic inference of ICD-10 codes from German ophthalmologic physicians’ letters using natural language processing. Sci Rep. 2024 Apr 19;14(1):9035. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-59926-3

- Mao Y, Fung KW. Use of word and graph embedding to measure semantic relatedness between Unified Medical Language System concepts. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020 Oct 1;27(10):1538–1546. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocaa136

- Reimers N, Gurevych I. Sentence-BERT: Sentence Embeddings using Siamese BERT-Networks. In: Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on EMNLP and the 9th International Joint Conference on NLP (EMNLP-IJCNLP); 2019 Nov; Hong Kong, China. ACL; 2019. p. 3982–92. doi:10.18653/v1/D19-1410

- Mikolov T, Chen K, Corrado G, Dean J. Efficient Estimation of Word Representations in Vector Space. arXiv preprint 2013. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1301.3781

- Schroff F, Kalenichenko D, Philbin J. FaceNet: A unified embedding for face recognition and clustering. In: CVPR; 2015 Jun 7–12; Boston, MA, USA. IEEE; 2015. p. 815–23. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2015.7298682

- Sun W, Yan L, Ma X, Wang S, Ren P, Chen Z, Yin D, Ren Z. Is ChatGPT Good at Search? Investigating Large Language Models as Re-Ranking Agents. In: EMNLP 2023; Singapore. ACL; 2023. p. 14918–37. doi:10.18653/v1/2023.emnlp-main.923

- Pradeep R, Sharifymoghaddam S, Lin J. RankZephyr: Effective and Robust Zero-Shot Listwise Reranking is a Breeze! arXiv preprint. 2023. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2312.02724

- Pokrywka J, Jassem K, Wierzchoń P, Badylak P, Kurzyp G. Reranking for a Polish Medical Search Engine. In: Proceedings of the 18th Conference on Computer Science and Intelligence Systems; 2023. ACSIS Vol. 35, p. 297–302. doi:10.15439/2023F1627

Resources¶

- Poster PDF: wada

_medinfo2025 _poster .pdf - DOI: 10.3233/SHTI251227

How to cite¶

Wada S. Improving MedDRA/J Coding Accuracy with a Fine-Tuned Text Embedding Model. In: MEDINFO 2025. IOS Press. doi:10.3233/SHTI251227.

Last updated: 2025-08